On 2nd July I had the privilege of interviewing the artist, curator and art historian Professor Eddie Chambers while he was here in the UK to launch and promote his new book, Black Artists in British Art: A History from 1950 to the Present (IB Tauris, 2014).

We met at the Ikon Gallery in Birmingham, where his installation piece African Icons (1987) was on display as part of a retrospective of works by UK contemporary artists – titled, As Exciting as We Can Make it: Ikon in the 1980s (2 July — 31 August 2014).

The focus of our conversation was an exploration and critical appraisal of the extent to which black British artists have experienced marginalisation and exclusion as regards their place within the nation’s contemporary visual arts canon, using Eddie Chambers’ own experiences of creating and exhibiting work since the early 1980s as a point of departure.

One of the most fascinating aspects of having a conversation about the arts with a professional as significant as Eddie Chambers is the depth and breadth of encyclopaedic knowledge that he brings to the table (and can summon up at will with pin-point accuracy!) about key players in the world of contemporary visual arts with whom he has collaborated to produce outstanding exhibitions symbolic of the UK’s ‘New Black Aesthetic’ of the past 30-40 years, but also his academic expertise on the visual arts history of the Caribbean and its diverse diasporas spanning many generations. For example, he shared several interesting insights about past curatorial work with individuals and collectives such as:

- Frank Bowling OBE, RA (b. 1936) – the Guyanese-British painter who (among many of his significant achievements worldwide) was awarded the Grand Prize for Contemporary Art at the first international arts festival held in Dakar, Senegal (1966), and in 2005 became the first black British artist to be elected a Royal Academician.*[1]

- The Wolverhampton Young Black Art Group and the Pan-Afrikan Connection (later renamed the BLK Art Group), founded by Eddie Chambers, Keith Piper and Donald Rodney in the early 1980s

- The Black-Art Gallery, Finsbury Park (London), 1983-1993 – which hosted many pioneering exhibitions under the directorship of Shakka Dedi, and then later Marlene Smith; from Heart in Exile (1983) through to Colours of Asia (1992).

In addition to this chronological survey of people and events, two key issues relating to UK arts policy and practice also emerged:

- Firstly, Eddie Chambers felt that, irrespective of the relative aesthetic merits and technical attributes of any individual artist’s work, black British artists of African, Asian or Caribbean descent were more regularly subjected to ‘erasure’ as regards their exclusion from historical records concerning the ‘mainstream’ British visual arts canon, and also the lack of any institutional commitment towards collating and maintaining comprehensive research collections about black British artists’ portfolios within the most important national archives and repositories pertaining to modern and contemporary visual arts (e.g. Tate’s permanent collections and the Arts Council Collection (ACC), etc.).

- Secondly, black British artists’ work has tended to be ‘de-normalised’ by the actions and interventions of the DCMS, Arts Council England, the UK’s national museums and galleries and other major arts organisations – primarily because of the tendency to only focus on the funding, promotion and wide-scale acknowledgement of British art produced by African, Asian and Caribbean diaspora artists during specific festivals or events associated with BME community histories and heritage, or on specific commemoration dates/anniversaries within the cultural calendar. The recent ‘Abolition 200’ events and the ACE-funded bi-annual ‘Decibel’ diversity showcases were both cited as particularly problematic examples from the recent past which – even though some small-scale and individualised successful outcomes were able to emerge via these funding streams and programmes – only served to further entrench marginalisation as a norm for minoritized artists, masked (of course) by the brief instances of ‘festivalised hyper-visibility’ bestowed upon a select few.

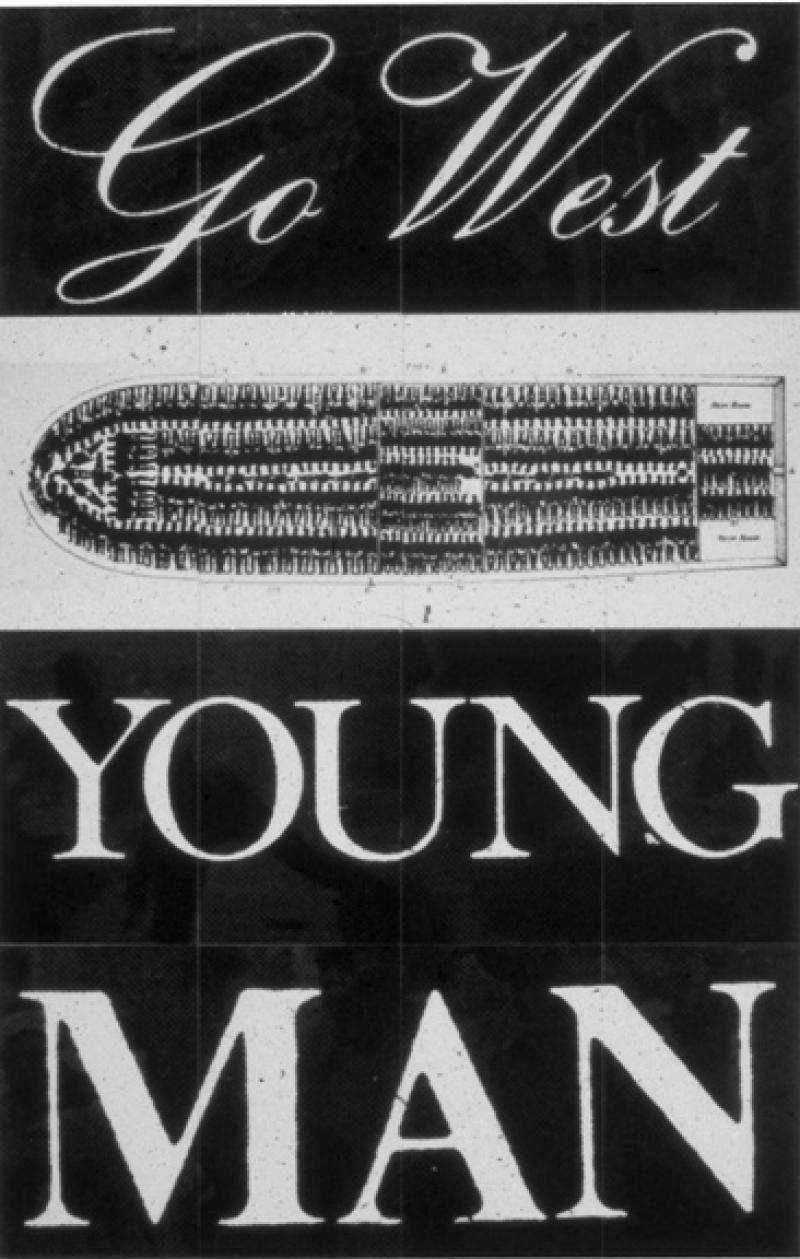

Despite the above (& other) problematic issues inherent within the wider arts and culture sector, I was able to reflect positively on (and express my own personal thanks to Eddie Chambers for) the many ground-breaking artworks produced by him and his close circle of fellow artists over several decades, which (in their own unique ways) all served as empathetic creative responses to some of the pivotal socio-political struggles and resistances experienced by African diaspora men and women worldwide – notably: The Destruction of the National Front (1979-1980) by Eddie Chambers; Go West Young Man (1987), by Keith Piper; and Sharpeville, Paris, London, New York (c.1990) by Simone Alexander.

Eddie Chambers is to be commended for everything he has strived to do over several decades (and continues to do) to prevent the above-mentioned ‘erasure’ from becoming the reality for future generations of black British contemporary artists – not least because of his pioneering development of the African and Asian Visual Artists’ Archive (AAVAA) back in the 1980s (which is accessible online via the Diversity Art Forum’s VADS (Visual Arts Data Service) website, but also because of the excellent books he writes to ensure that we have a comprehensive library of secondary literature that discusses the portfolios of British artists like the names that follow (among many, many other ‘pre-‘ and ‘post-Windrush’ painters, sculptors, photographers, installationists, etc.) in thoughtful and nuanced ways: Simone Alexander, Frank Bowling, Vanley Burke, Denzil Forrester, Amanda Holiday, Errol Lloyd, Tam Joseph, Mowbray Odonkor, Eugene Palmer, Tony Phillips, Marlene Smith, etc.

Although the title of the new book implies that the timeline in focus only relates to mid-to-late-20th and early-21st century art histories, the actual archival content spans over 200 years of documented black British creativity; ranging from expert introductory analysis of early 19th-century prints depicting the London street performer Joseph ‘Black Joe’ Johnson wearing an elaborate hat sculpture of HMS Nelson (c. 1815), through to Yinka Shonibare’s spectacular 4th Plinth contemporary art commission of Nelson’s Ship in a Bottle in the 2010s!*[2]

Notes:

* [1] For a full artist’s biography about Frank Bowling, see http://frankbowling.com. Essays about the retrospective exhibition of Frank Bowling’s paintings curated by Eddie Chambers are also documented in: CHAMBERS, E., GAYFORD, M., GOODING, M. & POUPEYE-RAMMELAERE, V. 1997. Frank Bowling: bowling on through the century: a major touring exhibition of recent paintings, [London], [Arts Council].

* [2] An early etching of Joseph Johnson wearing the model of HMS Nelson – titled, ‘Effigy of Joseph Johnson’ (1815) – was produced by John Thomas Smith (a former Keeper of the Prints in the British Museum) and is discussed in the foreword to Eddie Chambers’ afore-mentioned new book, alongside a photograph and commentary about Yinka Shonibare’s 4th Plinth commission, Nelson’s Ship in a Bottle (2010-2012). Both visual images serve as a framing device for Eddie Chambers’ contextualisation of the history of African diaspora artists’ contributions to British cultural life over several centuries. See the foreword, Celebrating Nelson’s Ships, in: CHAMBERS, E. 2014. Black artists in British art: a history from 1950 to the present, London, IB Tauris. pp. xii-xvi.

References:

CHAMBERS, E. 2014. Black artists in British art: a history from 1950 to the present, London, IB Tauris.

Website for further information: http://www.eddiechambers.com/ibtaurisbook/