Room 38a at the V&A Museum currently features a series of photographic reflections on black British lived experiences over a period of five decades, captured by selected African and Caribbean diaspora artists and photo journalists who came to prominence between the early ’50s and the 1990s.

The photographs are a sample of relatively recent acquisitions for the V&A’s growing collection of documentary and aesthetic works by black photographers, film-makers and conceptual artists whose portfolios and archives give prominence to images and representations of black British people as an integral feature of their oeuvres.

The artworks showcased in this single-room display range from pictures illustrative of the diversity and dynamism of black urban cultures across several generations – including impromptu and posed images by Armet Francis, Dennis Morris, Charlie Phillips and Normski; quartets of stunning black-and-white studio portraits by African luminaries such as Ghana’s James Barnor and Nigeria’s J.D. ’Okhai Ojeikere; and full-colour portraits of African Caribbean Londoners at home that were taken by Jamaican-born Brixton-based photographer Neil Kenlock during the 1970s.

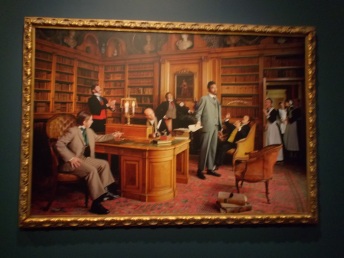

A particularly important element of the exhibition is the amount of space devoted to a suite of five, large-scale photographic tableaux positioned along the length of the left-hand-side wall – titled ‘Diary of a Victorian Dandy’ (1998), by Yinka Shonibare MBE (RA). In each of these theatrically assembled, gold-framed images the artist situates himself in the centre of scenes and decorative settings that have been ornately styled to look like rooms in the household of a wealthy, fashionable Victorian gentleman from the late-19th century. The times inserted as sub-headings suggest that each staging represents changing activities pursued over the course of 24 hours: with some scenes depicting the playful performance of boundary transgressions across differences of ‘race’, gender and class frozen in time by the photographer’s gaze; and others suggestive of acts of debauchery that re-enact the types of excessive behaviour illustrated in William Hogarth’s A Rake’s Progress (c. 1733-1735).

What is immediately noticeable about Shonibare’s self-representation as an elite and leisured Victorian dandy is his positionality at the heart of each image, made more noticeable by only selecting white sitters to perform the supporting (and ‘subordinated’) roles of his friends, lovers, attendants, and servants positioned in the more marginal and ‘parergonal’ spaces.

Collectively the tableaux are often interpreted as a “disruption of the essentialised positioning of black and white” in ways that question the notion of the ‘Other’ and the process of othering within British cultural life (see, for example, Tolia‐Kelly and Morris, 2004: 155).

From a socio-spatial perspective, Shonibare is also considered to be interrogating racial stereotypes by “using tactics of displacement and replacement – such as shifting the white male to the role of subaltern or inserting himself in a central role as a black dandy – so that there is a critical collusion of cultures” (Badinella and Chong, 2013: 25)

As the exhibition’s title suggests, Staying Power presents a strong and enduring visual narrative that spotlights the various ways photographers of African and Caribbean descent have successfully challenged and counteracted the gaze and label of ‘the Other’ as a direct response to the fall of empire, decolonization, independence and the possibilities of post-colonial re-awakening.

My only criticism is that more could (and should) have been done to increase the representation of works created by black women photographers in this display – as the portraiture of Jamaican-born Birmingham-based photographer Maxine Walker is the only portfolio on show representing the black female gaze from behind the lens. However, several portraits by Jennie Baptiste and a collection of self-portraits captured in rural landscapes by the internationally renowned conceptual artist Ingrid Pollard do feature in the companion exhibition to Staying Power that is on display at the Black Cultural Archives in Brixton until 30th June 2015.

The V&A’s current selection of images from the Staying Power acquisition project will be displayed until 24 May 2015.

REFERENCES:

BADINELLA, C. & CHONG, D. 2013. Contemporary Afro and two-sidedness: Black diaspora aesthetic practices and the art market. Culture and Organization, 1-29.

TOLIA‐KELLY, D. & MORRIS, A. 2004. Disruptive aesthetics?: revisiting the burden of representation in the art of Chris Ofili and Yinka Shonibare. Third Text, 18, 153-167.

ADDITIONAL NOTES AND WEB LINKS:

The title Staying Power was chosen to reference Peter Fryer’s important research into the longevity of the black African and Asian presence in Britain since the Roman era, and the under-acknowledgement of African, Asian and Caribbean contributions to British cultural life – first published in 1984 as ‘Staying Power: The History of Black People in Britain‘ (Pluto Press). The text was reprinted in 2010 , and extracts of the full-text can be read online via Google Books.

Further information about the Staying Power exhibition is available online via the Victoria and Albert Museum website: http://www.vam.ac.uk.

All the exhibition images featured in this blog post were taken at the V&A Museum by Carol Dixon (06/03/2015).

4 responses to “Staying Power: Photographs of Black British Experience 1950s-1990s (V and A Museum, London)”

As a former art museum docent, I think your blog is fantastic! http://lilypupslife.wordpress.com/

LikeLike

Thank you for the positive feedback!

LikeLike

I went to see the photographs and the V&A, it brought back sweet memories, the ‘Staying Power’ exhibition is FANTASTIC!!! a MOST SEE!!

I am a student studying photography and found the whole thing inspiring. ( if you could give me any help to contact any of the photographers I would be grateful. Akinda

LikeLike

Thank you for posting a comment on Museum Geographies, Akinda. I am delighted that you had the opportunity to see the exhibition and were as inspired as I was. One way of getting in touch with some of the photographers featured in the Staying Power ensemble is to write to them via the photography collective ‘Autograph ABP’ c/o http://autograph-abp.co.uk/. The website has an online form to submit queries and feedback. The ‘ABP’ stands for Association of Black Photographers, they have their base at Rivington Place in London and have an international remit to further interest in photography that addresses issues of identity, ‘race’ and the lived experiences of African diaspora communities worldwide. Best wishes, Carol

LikeLike