During mid-August 2017 I was very pleased to visit the Gare Saint Sauveur in Lille to view curator Simon Njami’s thought-provoking exhibition of photographs, paintings, films, sculptures and architectural installations by 30 contemporary visual artists from continental Africa and the African diasporas. This spectacular and wide-ranging group show – Afriques Capitales: Vers le Cap de Bonne-Espérance [Capital Africas: Towards the Cape of Good Hope] (Gare Saint Sauveur, Lille, France, 6th April – 3rd September, 2017) – was conceptualised and presented as the second chapter (or, ‘Episode Two’) of a curatorial project that began at the Grande Halle de la Villette in east Paris, and was later transposed and repurposed to fit this alternative setting of a disused freight goods railway terminal on the outskirts of Lille.

Since first becoming aware of Simon Njami’s writing and critical analysis of modern and contemporary African art, his editorship of the celebrated art magazine Revue Noire, and his extensive international curatorial practice over the past two decades, I have subsequently followed his progress with keen interest – making regular visits to different exhibition spaces and institutional settings to immerse myself in the stories and assemblages he and his contributing artists generate to provoke new discussions and dialogues about aspects of the universal human condition. All these observations and experiences are, of course, considered and refracted through the complex prism (or ‘optic‘) of colonialism, and its enduring legacies in the present day – reflected upon at the site of the individual (as regards my personal, affective/emotional responses to each artwork); at the level of the nation-state; as a trans-continental conversation between Europe as the site of display, and Africa (including its diasporas) as the creative locus and originating point of departure for these featured exhibits; and also in terms of global discourses about travelling and journey-making to the many elsewheres represented in the featured displays – both near and far; real and imagined.

As soon as I walked through the entrance gates at Gare Saint Sauveur and saw the large-scale architectural structure of Egyptian artist Moataz Nasr’s installation, “I am Free” (2012), I knew I was entering a creative space where the curator had encouraged all the participating visual artists to be bold and expressive on a monumental scale: in other words, giving all the artists and collectives complete licence to think creatively without limits and, in turn, exhort and inspire visiting audiences walking through the exhibition space to respond in kind. In consequence, I required no prompting to run to the top of the temporary staircase erected at both ends of the white-walled, Minaret-like construction to stand on its central platform with my arms outstretched, enacting the declarative statement “I’m Free!” In doing so, I was also able to imagine that I had become one with the vast, black painted bird’s wings, beautifully and fluidly drawn at either side of the neon lighting, and taken flight into a different realm.

Once inside the main building, a video-taped welcoming message from curator Simon Njami set out his overarching vision for the project – characterised by the evocation of intensely poetic journey-scapes and creative voyages of experimentation, seemingly pursued beyond the realms of our physical and situated existences (i.e. without the geopolitical restrictions of encountering international border-checkpoints) and moving seamlessly into new and alternative places and spaces of the imagination:

“Les plus beaux voyages sont ceux qui peuplent notre enfance […] Je m’imagine cingler, toutes voiles dehors, depuis Lille jusqu’ou Cap de Bonne-Esperance. La destination, a vrai dire, importe peu. Seule me motive cette espérance contenue dans le nom de cette ville Afrique du Sud, aux confins du continent.”

[The most beautiful journeys are those which populate our childhood […] I imagine myself travelling, with all the sails outstretched, from Lille to the Cape of Good Hope. The destination, to tell the truth, is of little importance. What motivates me is the hope contained in the name of this South Africa city, located at the edge of the continent.]

Simon Njami – Curator / Commissaire de l’exposition

What follows in this review is a selection of the photographic images taken as I meandered through the exhibition space over the course of a two-hour visit, reflecting on some of Njami’s intellectual provocations (expressed in reference, and homage, to the philosophy of Ernst Bloch) – including the key question, “How can we create a world in which difference can finally be perceived as a source of wealth and not as a loss or a violation?” [“Comment fabriquer un monde dans lequel la différence puisse enfin être perçue comme une richesse et non comme une perte ou un viol?”] – and also formulating and expressing my own interpretations of the exhibits.

The sequence of photographs reflects my self-directed route through the exhibition space, capturing a selection of the works presented by the 30 established and emerging contemporary visual artists and collectives from continental Africa and the African diasporas. Similarly to the first episode of Afriques Capitales that I saw displayed in Paris earlier in 2017 (and wrote about in my article, Afriques Capitales: A Barthesian multiplicity of cities presented at La Villette in Paris), the exhibition included well-known internationally recognised artists such as Abdoulaye Konaté, Meschac Gaba, Hassan Musa and El Anatsui, but also a number of younger contemporary visual artists exhibiting in Europe for the first time, such as the installationist Paul Alden Mvoutoukoulou from Congo-Brazzaville (b. 1987).

Sharing the space with Hassan Hajjaj’s street vendors, positioned along an adjacent wall near the station’s main entrance was a second work by Angolan artist Kiluanji Kia Henda – titled, “The Great Italian Nude” (2010), with very similar visual and titular references to artist Tom Wesselmann’s “The Great American Nude” (MoMA, 1965). The bold and provocative subject matter of this photographic artwork signified a much more visceral confrontation with the physical presence of black and brown people resident and settled in Europe as an established part of cultural life in the West – or, as the photograph suggests, as commonplace, established and matter-of-fact as the decorative furniture on which Kiluanji Ki Henda’s masked, nude male sitter is reclining.

In the central area of the exhibition space, Simon Njami chose to feature a diverse range of very striking architectural installations, two of the most prominent and thought-provoking are illustrated in the interior shots shown below. Firstly, Kinshasan metalwork sculptor Freddy Tsimba’s work – Forgotten’s Tears (2013) – shows a series of group characters made out of twisted metal spoons and shown roasting on or racked up and adjacent to several barbeques. The written interpretation narrative accompanying the work suggests that it is symbolic of the dualities of heaven and hell, angels and demons, and also the in-between state of purgatory. The work is intended to provoke questions about the nature of suffering and survival on earth, especially when considered in relation to the hopes and deferred rewards of a more fulfilling afterlife once humans leave the earthly realm.

Secondly, and in stark contrast to Tsimba’s purgatorial vision, the Beninese conceptual artist Meschac Gaba presented the monochrome sculptural installation Sweetness (2017) – featuring a fantastical white urban landscape made entirely out of refined blocks of sugar shaped into recognizably iconic architectural monuments from different regions and cultures of the world.

Another important architectural sculpture erected in the centre of the exhibition space was a five-room installation known as “Hotel Africa,” each separate space featuring works by the artists Hassan Hajjaj, Andrew Tshabangu, Gopal Dagnogo, and Pume Bylex. The Hotel’s reception area, designed and defined as a “Salon” (2017) by the Moroccan artist Hassan Hajjaj, encouraged visitors to sit in a space reminiscent of a North African tea room, with walls lined with news print and make-shift seats created using square cushions on empty, plastic Coca-Cola bottle crates. The Salon, just like the other areas of Hotel Africa was a space of welcome and relaxed conviviality to encourage people to dwell and converse in the setting for extended periods of time.

A particular signature of several of Simon Njami’s group exhibitions is the way he foregrounds and celebrates innovative and experimental photography and film-based installations by visual artists from all regions of the African continent and the wider diasporas. Afriques Capitales/Capital Africas was no exception, and the Hotel Africa installation provided a suitable location to juxtapose the contemporary photo-journalism of artists such as Delio Jasse alongside more intimate and poignant fine art images by the Turin-born, Paris based photographer Nicola Lo Calzo (creator of the series “Tchamba”, 2011-2017, taken in Benin and Togo, from which the images shown below were sourced).

Positioned outside the Hotel Africa, but also enclosed within a set of display alcoves designed to give the appearance of a group of inter-connected railway carriages positioned along an entire length of the exhibition space, were a series of moving, film-based installations by the artistic duo Mwangi Hutter – namely the Kenyan video installationist Ingrid Mwangi and her German husband Robert Hutter. The installation “Turquoise Realm” (2014) projected a sequence of images of the artists lying separately on a bed inside a turquoise-painted room. For the most part, the central screen within this trio of projections showed an empty bed. However, over time, both artists finally emerged in the centre of the video-based ‘triptych,’ wrapped in each other’s arms on the bed, using different filmed sequences superimposed on top of one another to give the appearance of a physical union but, in reality, represented an intricate layering and montage of separate filmed recordings of their individual movements.

The final series of artworks viewed towards the rear of the exhibition space proved to be some of the most interesting sculptural works within the entire selection. The first, Scott Hocking’s installation “Babel” (2015-2017), was assembled in the most remote area of the old freight terminal, and enclosed behind a large pane of glass to encourage viewers to pause and reflect on the concepts of time, language, mythology, alchemy and perception, through the artist’s combining of artefacts and ephemera sourced from the previous installation site in Detroit combined with reclaimed and recycled materials found on site in Lille.

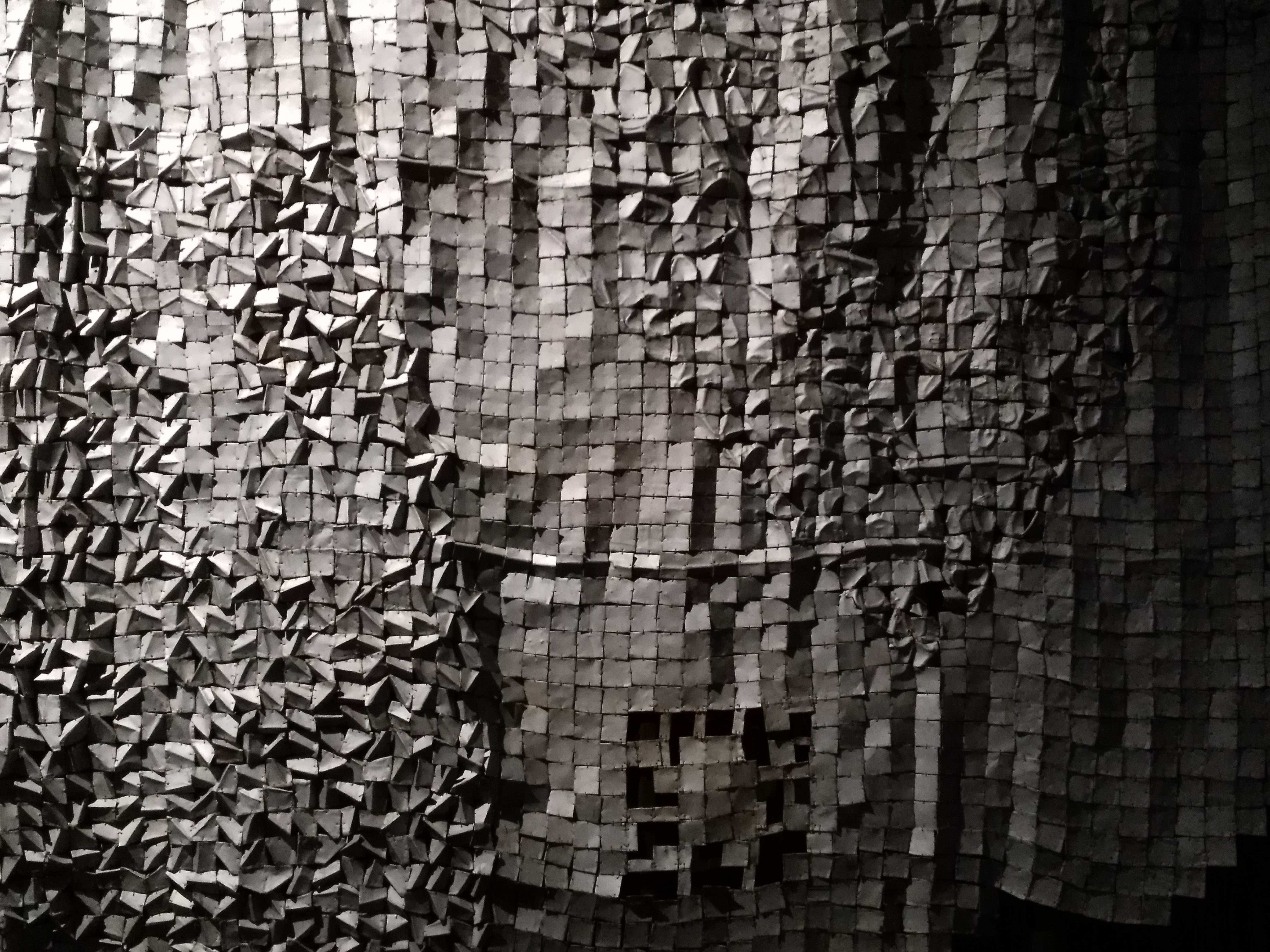

The last set of sculptures were a pair of wall hangings created by the Ghanaian textile sculptor El Anatsui, renowned for his ability to construct vast textiles from recycled pieces of metal and plastic (such as used bottle tops and discarded phone cards) intricately stitched and bonded together to transform waste materials into monumentally sublime works of beauty. Every element of El Anatsui’s creative process is geared towards communicating concerns about the relationships and interdependencies between histories of colonial exploitation and the aftermath of colonialism’s devastating socio-political, economic and environmental legacies – including the over-consumption of natural resources, environmental pollution and a lack of sustainable waste management practices worldwide.

For anyone interested in finding out more about Afriques Capitales/Capital Africas, a full-colour, 200-page illustrated catalogue to accompany both episodes of the exhibition staged in Paris and Lille is available to purchase, c/o Kehrer Verlag.

WEBSITES AND LINKS FOR FURTHER INFORMATION:

Dixon, Carol Ann (2017) Afriques Capitales/Capital Africas: A Barthesian multiplicity of cities presented at La Villette in Paris – an exhibition review, published via Museum Geographies in May 2017.

Njami, Simon (2017) Afriques Capitales/Capital Africas, Exhibition Catalogue. Heidelberg and Berlin: Kehrer Verlag, in association with La Villette and Lille3000. 208 pages. 115 colour and b&w illustrations. ISBN: 978-3-86828-792-9. URL: https://www.kehrerverlag.com/en/afriques-capitales-capital-africas-978-3-86828-792-9

An interview with curator Simon Njami, discussing his work on Afriques Capitales/Capital Africas in conversation with the journalist and cultural commentator Virginie Ehonian:

https://africanlinks.net/2017/03/14/lafrique-a-la-villette-3-questions-a-simon-njami-extrait/ (See also Virginie Ehonian’s extended interview with Simon Njami for Africultures).