I am pleased to present a selection of images taken during my review of the Royal Academy’s exhibition, Entangled Pasts, 1768–Now: Art, Colonialism and Change (Burlington House, Piccadilly, London, 3 February – 28 April 2024).

This extensive visual arts presentation offered an octagonal main gallery and 10 additional rooms of thematic assemblages and juxtapositions – each selection comprising paintings, drawings, sculptures, film-based installations, archival documents and other ephemera reflecting the many complexities and legacies of empire represented by Royal Academicians over several centuries. Through sub-themes connecting the RA’s holdings of artworks, archives and Academicians’ papers to the UK’s imperialist and colonial past, the narrative also aligned this visual and textual history with the institution’s more recent policy progressions and exhibiting practices that reflect a move towards decolonisation of this long-established and learned space.

My selection of photographs was taken during a two-hour tour of the galleries at Burlington House – choosing to visit on 3 April 2024 in the final few weeks before the exhibition’s closure, making way for the annual hosting of the RA’s Summer Exhibition (18 June – 18 August 2024).

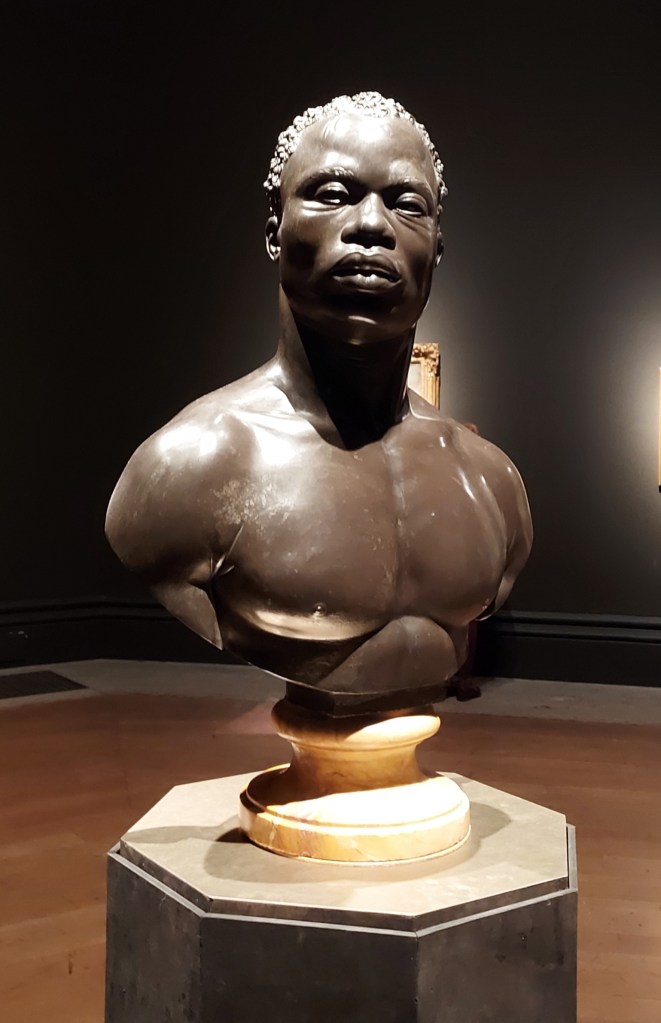

The large, free-to-view sculptural installation of ‘The First Supper’ (Galaxy Black), 2023, created by Bahamian-born contemporary conceptual artist Tavares Strachan, provided a visually awe-inspiring and captivating courtyard assemblage of bronze, black patinated and gold-covered figurative sculptures to open the show, carefully arranged in symbolic reference to Leonardo da Vinci’s 16th century depiction of the ‘The Last Supper.’

Tavares Strachan’s decision to choose twelve, inter-generationally and internationally significant characterisations of pioneering figures with African heritage – drawn from all the centuries in focus in the exhibition, and also the globally dispersed African diaspora – meant that this bold, life-sized dining scene of a dozen figures, presented in suspended animation, rightly commanded significant mainstream news headlines and generated a multiplicity of re-shares on social media to spotlight the installation as a ‘must see’ piece.

The recognisable 3D silhouettes of these twelve inspirational figures transformed the viewing into an exhilarating immersive experience of ‘say-what-you-see’ interactivity, as the familiar features of the seated dinner guests provoked audible whoops of recognition from an ever-changing crowd of passers-by. The conjuring up of image-based memories and biographical details to assign the correct names, histories and lived experiences to the figures was based on an internalised recollection of their phenotypical features, hairstyles, period attire, and accessories. The ease of the identification signaled each individual’s status as a well-known figure (celebrated for pioneering achievements in the fields of science, politics, literature, music, medicine, the visual arts, legislation, human rights activism and community advocacy) and inevitably sparked excited conversations, beaming smiles and numerous ‘selfies’ as spectators took turns to insert themselves into this thought-provoking, Afro-futurist gathering of Black luminaries.

Beyond the courtyard, it was equally inspiring to spend time contemplating the thematic presentations inside the first-floor galleries at Burlington House, which brought together 100 carefully selected artworks and extracts from literary narratives – spanning four centuries, trans-oceanic geographies, and generations of socio-cultural entanglements.

Each of the featured juxtapositions prompted an interrogation and reckoning with the many ways art is imbued with immense power to influence our responses to narratives of empire, enslavement and resistance, abolition, indenture, colonialism and their afterlives and ripple effects felt today.

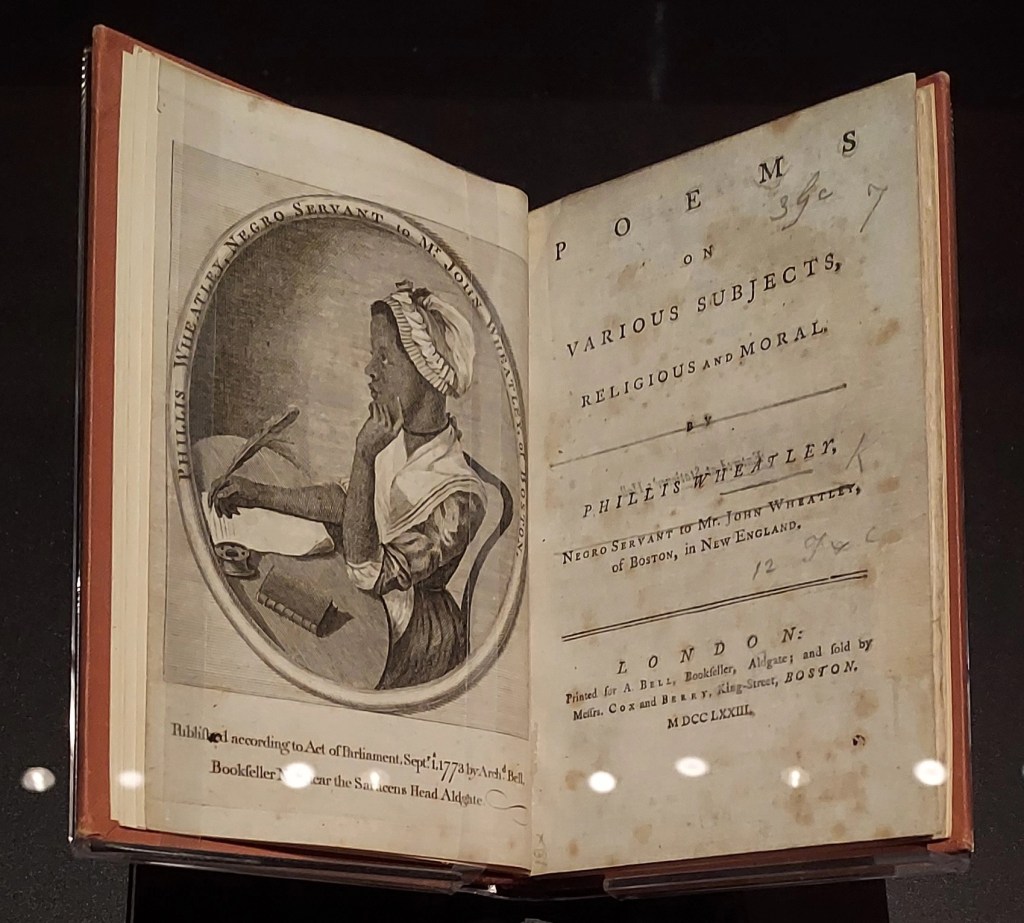

Additionally, the inclusion of original letters written by African-British abolitionist (Charles) Ignatius Sancho (1729-1780), as well as a period copy of formerly enslaved African American writer Phillis Wheatley’s 18th century book of poems (the first poetry collection to be published in Britain by a Black woman, in 1773) were some of the most important text-based exhibits displayed on loan from the British Library’s collections, which helped to contextualise and augment the RA’s visual presentation. These rare and immeasurably precious anti-enslavement narratives, penned by Black men and women decades before the abolition movement achieved mainstream momentum, also served to foreground the agency and epistemic authority of pioneering scholars of colour in the long struggle to bring the nefarious trans-Atlantic trade and plantation-based enslavement to an end.

Exhibition highlights

Two featured sculptures by Nigerian-British installationist Yinka Shonibare CBE both played with historical conventions that depict human progress and personify the concept of justice as a woman.

Both of Shonibare’s installations were, for me, the standout artworks in this exhibition, and worked in harmony with each other as pieces from his internationally recognized globe-headed series of works, specifically: “Woman Moving Up” (2023), shown in the section of the thematic presentation titled “Beauty and Difference”; and the pedestalized, mixed-media sculpture “Justice for All” (2019), positioned later on in the presentation and shown in dialogue with Olu Ogunnaike’s re-sized replica of Trafalgar Square’s empty 4th plinth made from recycled shards of wood – “I’d Rather Stand” (2022).

Regarding the former, the artist’s signature symbolism of a brown-skinned mannequin dressed in a Victorian era bustle dress and seemingly carrying the weight of the world in a traditional leather grip at one hand and a large Gladstone bag in the other speaks to the characteristics of human self-determination. She’s ascending a set of steps crafted with ornately styled balusters – architecturally echoing the design of the central stairway leading up into the gallery from the RA’s Piccadilly entrance. The woman’s determined and unbowed rise continues – despite the heavy baggage she is carrying, laden with cultural signifiers depicting the land masses fought over (shown on postcards), the raw materials extracted and the commodities traded over centuries of Britain’s troubled and violent imperialist past.

“The arc of the moral universe is long,

Dr Martin Luther King Jr. (1929-1968)

but it bends towards justice.” (Selma, USA, 1965)

The positioning of both works by Shonibare posed important questions about the challenges of striving to achieve one’s full potential when the historical legacies and racialised inequities fueled by societal prejudice, exclusion, ‘misogynoir’ and other forms of anti-Black hatred still bear down heavily on us. Clearly, the “arc of the moral universe” is taking a very long and circuitous journey in order to bend towards the truth and justice for all those whom this figure represents.

The traumas and triumphs of trans-oceanic crossings: past, present and future…

The concluding galleries focused on a selection of contemporary visual artworks curated by Rose Thompson that reference the powerful significance of bodies of water and trans-oceanic journey-making – by force, but also by choice – in our generational stories of migration, re-location and diaspora formation. The geo-political and socio-cultural dynamics of these overseas movements represented in this montage of works (below) helped me to appreciate the physical force, the spatio-temporal significance, and the emotional and affective power of water crossings.

The tiled gallery of four images shown above features (from the top): (1) A still from the three-channel HD video installation, “Vertigo Sea” (2015) by John Akomfrah; (2) A close-up of one floating figure from the artwork “Stabilising Spheres” (2014), by Ellen Gallagher – part of a series of works by the Rhode Island-born artist themed around the Drexciya myths and her concept of the “Watery Ecstatic”; (3) Detail from the 18th century painting “Watson and the Shark” (1778) by Anglo-American painter John Singleton Copley; (4) “No World, from An Unopened Land in Unchartered Waters” (2010), by Kara Walker.

Concluding thoughts…

I’m really glad I waited until the opening buzz surrounding this high-profile show had died down before taking my time to view the exhibition in its final weeks – browsing relatively crowd-free galleries, and also having unrestricted access to all the interpretation literature displayed alongside the exhibits.

It is always a pleasure to see a show like ‘Entangled Pasts,’ which gives prominence to the work of artists of colour, and encourages a diverse group of diasporic Academicians to influence the way the curatorial narrative is written. Moreover, I was also encouraged to learn that an institution as long-established as the RA is striving to embrace more diverse representation and polyvocality within its curatorial teams, even if still not (as yet) employing Black/Brown scholars within its most senior tiers of leadership and governance. However, I do feel that some aspects of the overarching curatorial narrative lacked courage, particularly in the way the thematic storytelling within parts of the exhibition became more concerned about offering a hagiographic treatment of the RA’s connections to British imperialist and colonial history, instead of articulating truly honest and decolonial perspectives on the lived realities and legacies of inequity wrought by the British Empire.

All that being said, if you are reading this review before the closure date (28 April 2024), I recommend visiting the RA to view ‘Entangled Pasts’ in situ, because the scale of the presentation is a sight to behold. However, if you’re unable to get there in person, then I do hope this illustrated critique has provided a useful visual impression of the varied juxtapositions of historical and contemporary artworks, poetic interludes and archival materials – spanning the period from the mid-18th century to now – assembled to give us much to consider and unpick over the course of this politically and culturally entangled timespan.

Photo credit: Dr Donalea Scott.

Further reading and web links

Akinkugbe, Alayo (2024) “Beauty and Difference: Models, Exhibitors, Presidents: Constructing Whiteness,” in the exhibition catalogue for Entangled Pasts, 1768-Now: Art, Colonialism and Change. London: Royal Academy Publications, pp. 143-163.

Lee, Sarah (2024) “Sites of Power: Portraits and Presence,” in the exhibition catalogue for Entangled Pasts, 1768-Now: Art, Colonialism and Change. London: Royal Academy Publications, pp. 53-63.

Locke, Hew (2024) “Armada” – Film clip and artist’s audio voiceover for his flotilla-based installation “Armada” (2017-19), displayed in the Royal Academy exhibition Entangled Pasts, 1768-Now: Art, Colonialism and Change. Source: Royal Academy of Arts YouTube Channel.

Strachan, Tavares (2024) The First Supper – Film clip and audio-voiceover of contemporary conceptual artist Tavares Strachan discussing his sculptural installation, ‘The First Supper’ (Galaxy Black), 2023, displayed in the Annenberg Courtyard at the Piccadilly entrance to the RA. Source: Royal Academy of Arts YouTube Channel.

Royal Academy of Arts (RA) exhibition overview about Entangled Pasts, 1768-Now: Art, Colonialism and Change [Online] – https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/exhibition/entangled-pasts

Thompson, Rose (2024) “Crossing the Waters: The Aquatic Sublime,” in the exhibition catalogue for Entangled Pasts, 1768-Now: Art, Colonialism and Change. London: Royal Academy Publications, pp. 165-178.