The exhibition Nigerian Modernism: Art and Independence (Tate Modern, London – 8 October 2025 – 10 May 2026) examines the history and dynamism of modern art in Nigeria throughout the 20th century, with a particular focus on how the transitional decades of anti-colonial struggle, independent state formation and post-1960 expressions of new nationhood were envisioned and communicated via the fine arts, architecture, fashion and styling and other forms of creative and cultural production.

Displayed on Level 3 of Tate Modern’s Natalie Bell Building, this expansive presentation of painting and sculpture, pottery, photography, archival materials and published periodicals provided insights into the emergence, growth and diversification of artistic modernism in Nigeria during a period of significant political, socio-economic and cultural change.

Led by Osei Bonsu (Senior Curator, International Art, Africa and Diaspora, Tate Modern), the stories within the exhibition were told throughout nine inter-connected rooms. Collectively, the assembled artworks and interpretation narratives provided an overarching chronology and a selection of thematic interludes through which to consider the creative outputs and influences of notable individuals, collectives, art schools, networks and art-political movements.

Nine Rooms: From Figuring Moderninty to Painting in Darkness

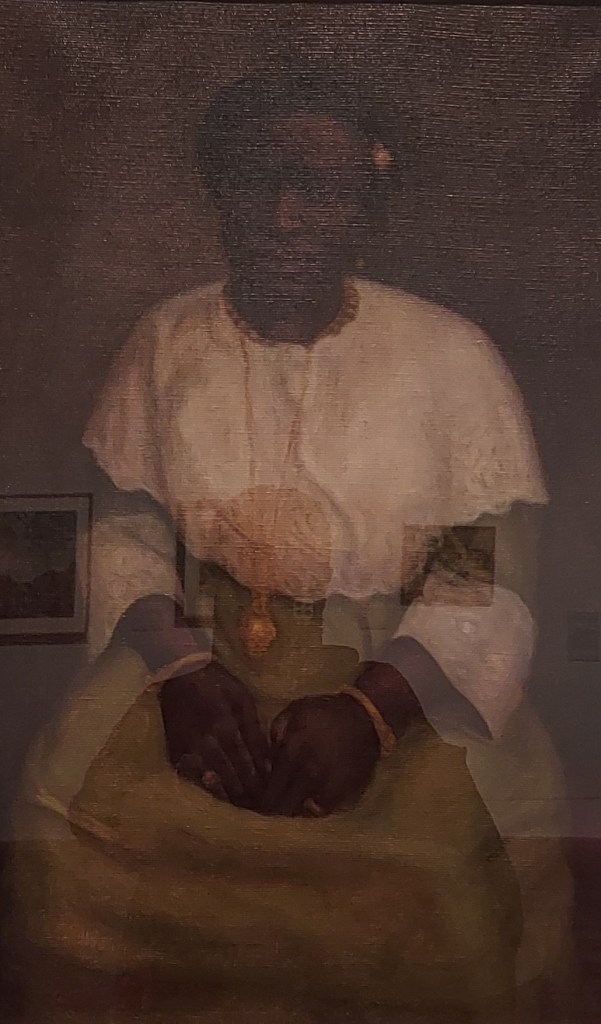

Commencing with a focus on early-20th century figuration, the opening sections showcased works by pioneering modernists, such as portraitist Aina Onabolu (1882-1963) and wood carver Olowe of Ise (1875-1938).

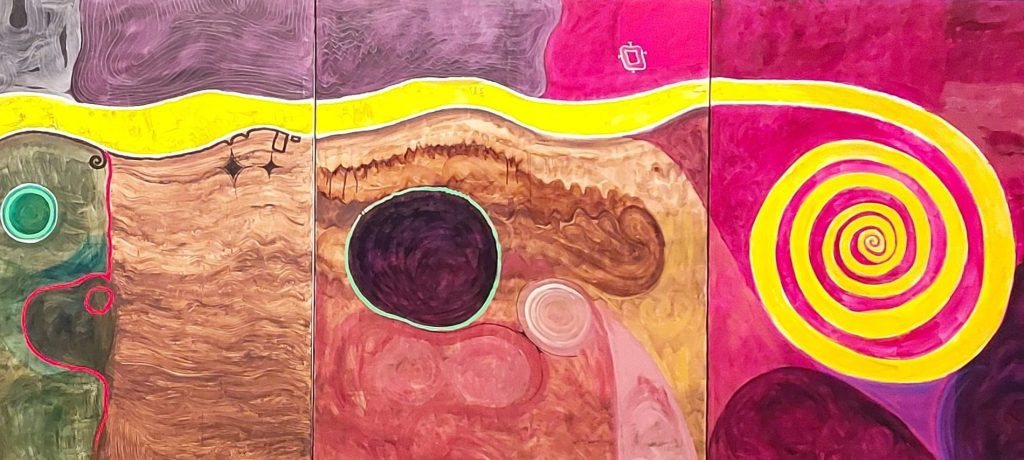

Subsequent rooms presented celebrated works from the portfolios of internationally renowned luminaries – most notably, painter and sculptor Benedict Enwonwu (1917-1994) and pioneering female potter and ceramicist Ladi Kwali (1925-1984). The concluding selection also showcased a solo series by painter and print-maker Uzo Egonu (1931-1996), known for producing highly engaging compositions that blurred the lines between abstraction and figuration.

The largest spaces in the middle of the exhibition grouped together works by alumni and affiliates of specific art schools, societies, activists’ collectives and art-political movements – including The Zaria Art Society, The Oshogbo School and the University of Nigeria, Nsukka. These sections also provided contextual information about key cities, regions, religious sites and political centres of influence in Nigeria throughout the decades in focus – documenting, for example, the cultural vibrancy of “Eko”/Lagos and the spiritual heritage of Osun-Osogbo in the south-western region.

Drawing on the exhibition’s titular sub-themes, my personal highlights are shared below and conclude with remarks about the significance of this show as an entryway for mainstream audiences seeking to engage more fully with global majority (worldwide and diasporic) contributions to artistic modernism beyond the West.

Figuring Modernity

Ben Enwonwu: Ghosts of Tradition

Ladi Kwali: Of Soil and Stone

New Art, New Nation: The Zaria Art Society

Zaria Art Society was established in the 1950s, founded by students at the Nigerian College of Arts, Sciences and Technology (NCAST) in Zaria. Most active between the years 1958-1962, the Society’s philosophy of “natural synthesis” underpinned the pro-independence and Pan-Africanist politics of its members, as well as their future-focused creative outputs. A combination of rebellious resistance to colonialist curricula and a willingness to build bridges between Indigenous and modern forms of cultural expression characterised the Society’s art-political activism and aesthetic innovations throughout that pivotal period.

Artworks by leading figures such as Uche Okeke (1933-2016), Demus Nwoko (b. 1935), Yusuf Grillo (1934-2021) and Jimo Akolo (1934-2023) featured prominently in this area of the exhibition. However, I was also delighted that pioneering women’s portfolios and biographies – which, historically, have tended to receive less attention – were foregrounded: including the critically acclaimed fine artists and teachers at NCAST, Clara Etso Ugbodada-Ngu (1921-1996) and Colette Olumbamise Omoghai (b. Uzebba, Edo State, 1942).

Eko

Referencing the former name for Lagos, “Eko” (which dates back to the port settlement’s early administration by the Benin Kingdom), this room celebrated the city’s vibrancy as a metropolitan meeting point and creative hub for exchanging ideas, for blending together diverse aspects of the nation’s cultural heritage and for birthing new forms of artistic expression in the post-1960 era of independence.

Enlarged archival images of modern urban architecture, collections of lifestyle magazines and artwork on the sleeves of popular Nigerian highlife records helped to evoke the cultural dynamism of post-colonial Lagos during the 1960s. These selections were positioned alongside fine art paintings by the abstract artist and muralist Erhabor Emokpae (1934-1984), sculptures by Okpu Eze (1932-1995) and Agboola Folarin, and a selection of hair art images from the iconic b&w photo series “Hairstyles” by J.D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere (1930-2014).

Festival of the Gods: The Oshogbo School

Signs of Life: The Nsukka School – Come Thunder

COME THUNDER

“Now that the triumphant march has entered the last street corners,

Remember, O dancers, the thunder among the clouds…

Now that the laughter, broken in two, hangs tremulous between the teeth,

Remember, O dancers, the lightning beyond the earth…”

– Extract from the opening lines of “Come Thunder” (1967), by poet Christopher Okigbo (1932-1967). An audio recording of the full poem provided a poignant soundscape for this section of the presentation about the Nigeria-Biafra War (1967-1970).

Concluding Reflections

Describing this exhibition on Nigerian Modernism as outstanding is an understatement. I came away feeling informed, inspired and also moved by the visual and textual poetics presented throughout the space. The clarity of the accompanying written interpretation helped to convey a plural, multi-layered and multicultural narrative – using selected spotlights on key individuals and art collectives to avoid overloading and overcrowding the galleries.

Most importantly, I welcomed the centrality of Nigerian creatives’ first-hand testimonies, referenced and quoted throughout the exhibition. These accounts were prioritised above the more typical practice in UK museums of over-reliance on readily available archival documents and publications about European art world allies and contemporaries based in continental Africa – such as, for example, German-Jewish writer and art scholar Ulli Beier (1922-2011), founder of the journal Black Orpheus (1957) and co-founder of the Mbari Artists Club in Ibadan (1961). In this way, Nigerians’ accounts of their own anti-colonial agency throughout the struggles for independence – and Black modernists’ perspectives on their own artistic self-representation (individually, as well as within collectives and movements) – rightfully maintained primacy of place throughout this insightful exhibition.

Nigerian Modernism continues at Tate Modern through to 10 May 2026.

Leave a comment